Going Public Kinda Sucks Now

And that changes everything.

A three-part series on private power and public markets — Part 1 of 3.In my last piece, The Signals That Move Stocks Aren’t Public, I argued that the forces moving public markets now originate in private companies; and that they surface in startups years before they bubble up to earnings calls, SEC filings, and carefully massaged CIO surveys. That post was the disciplined version of something much longer — 30+ pages, written late at night — until I startled myself awake and decided maybe a three-pager would be more humane (with a little help from my friends ChatGPT).

This piece kicks off a short series of deeper dives. Think: slices of the original, sculpted into something that looks new (and mostly is). First up: how we ended up in a world where the most important companies don’t trade and why this cycle isn’t just another temporary startup crush for Wall Street.

“In every major innovation cycle, banks suddenly remember startups exist…”

Sound familiar? If yes, you’ve been reading my stuff. If not, read on. I swear this is all brand-new content 🤐

Then banks act genuinely surprised that they matter. Not entirely different from big tech (ironically). But first… some history From the Porch (unironically).

Late ’90s: The Internet goes mental. Suddenly every bulge-bracket shop is hiring “Internet Analysts” mooching coffee chats in Palo Alto and chasing venture-backed IPOs. I should know… I was one of those analysts. Ferragamo tie, big paycheck, bigger ego, no experience, no clue. (Look down. That’s me circa 1998. Swear.)

2010s: Social/mobile/cloud (“Web 2.Ohhh!”) reshape the Internet. Banks spawn “unicorn roundtables,” convene venture-tech teams in Menlo Park, and build late-stage coverage desks. Private companies are treated as the next tranche of public stars.

Crypto era: Token desks, “blockchain strategy groups,” structured product for digital assets. Wall Street invests aggressively in next-wave hype. Then the cycle cools, a few people go to prison, desks reorganize, and the focus returns to EPS, dividends, and comp tables.

Different cycle, same story: Innovation heats up → Wall Street sprints toward the proverbial startup garage → market turns → back to earnings models and DCF purgatory.

“We’re getting back to our roots in tech innovation.”

– Every bank TMT head at every tech cycle top: circa 2000, 2012, 2017, and 2021.

But startups don’t exist for banks’ convenience (obviously) and innovation doesn’t follow quarterly EPS cycles (woefully). The Street chases private markets when it smells IPO fees and then wanders off when the hunting gets harder.

I don’t blame them – that playbook worked when staying private was (simply) the pre-IPO waiting-room.

But going public kinda sucks now.

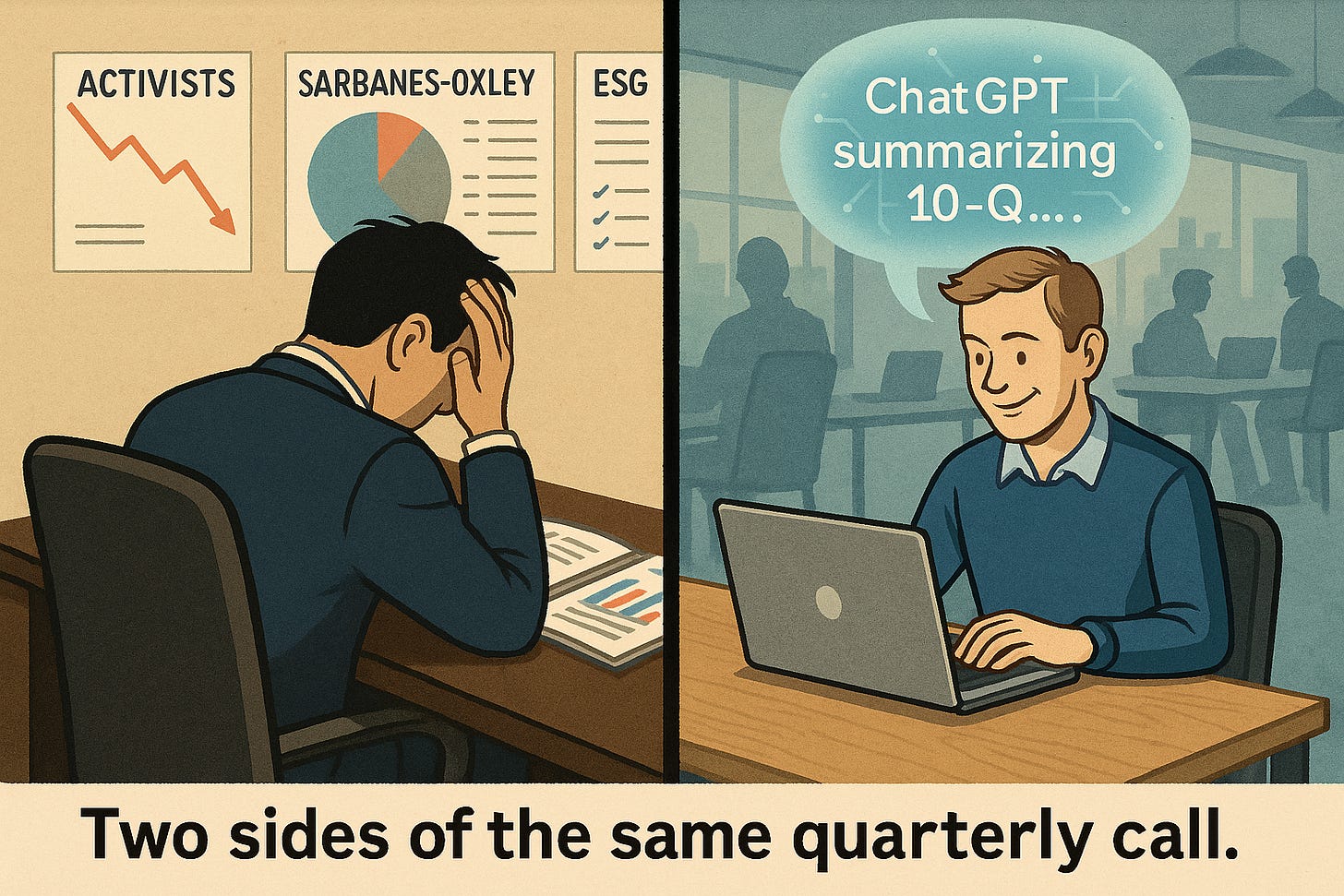

Today’s public markets resemble a compliance marathon in stiff (unironic) dress shoes. The regulatory load is heavier with Sarbanes-Oxley Act, ESG demands, activist pressure, quarterly disclosure treadmill. Being public now means navigating quarterly expectation inflation, investor activism, nagging overhead, and smart-ass, inexperienced analysts (broad)casting judgment on how you run a business they know nothing about other than what ChatGPT told them after a copy / paste sesh with an SEC filing.

Meanwhile, late-stage private capital matured. Tiger, Coatue, et al morphed from hedge to crossover funds when they started doing late stage venture. Big mutual funds like Fidelity and T. Rowe Price followed. Before long, other massive funds, sovereign wealth, corporates, and very (very) wealthy people filled the rest of the void. Suddenly, startups realized they don’t need public markets (yet). Founders would rather (and can) build in (relative) peace instead of living under the trigger-happy thumbs of meme-traders, dodging earnings whisper numbers blowing in the wind, and answering to compliance managers and legal departments.

Disagree? Here are the receipts:

The number of publicly traded US companies dropped from >8K in the mid-1990s to <4K by 2020 according to a report from researchers at the Tuck School of Business last year.

A Harvard Law paper from this year showed the US listing gap (companies that might go public versus those that do) grew by ~32% from 2012 to 2023.

Another study showed the number of public companies in 1996 was >8K, but fell to ~4,700 by 2023.

Implication for banks: If companies are staying private longer (or forever), the traditional pipeline of “private → IPO → coverage → underwriting” shrinks. To stay relevant, banks have to dig deeper earlier into the private realm.

This time is different because the giants are private.

Each previous cycle’s fling with startups was a fleeting crush. This time, that flirtatiously fleeting crush has become an existential need that, left unsatisfied, will toll each bank’s death knell. (Oof. I need a cigarette.)

For the first time, the most strategically important companies in technology — the ones moving markets, dictating capex cycles, and shaping geopolitical infrastructure — aren’t public. They are private, massive, and define the operating reality of the public markets. You can’t model the public-market side of these sectors without understanding this private core. Period.

The point here isn’t that banks “missed” these companies. Wall Street has always followed the money, and for decades the money lived on exchanges. The problem is that when the most important companies in technology are private, massive, and structurally insulated from public-market cadence, the old playbook breaks. You can’t understand Nvidia demand, cloud capex, payments economics, defense procurement, or data-center architecture by reading filings alone because the companies setting those curves don’t file them.

That’s what makes this cycle different. Private markets used to be the waiting room, but today they’re the control room.

In the next piece, I’ll go one level deeper and focus on a few companies themselves including OpenAI, Stripe, and SpaceX — which conveniently covers tech, financial services, aerospace, defense, and telecom.

Love this!